Segregation

and Variation in 1970s Belfast: A Study of Phonological Variation in Belfast

Urban Vernacular.

Sarah McLoughlin, © 2007.

This

article will examine English as it was spoken in inner-city Belfast in the

1970s, just after the commencement of the Troubles in 1969. Sporadic outbursts

of intercommunity hostility occurred before this date, but the severity of the

post-1969 conflict led to increased segregation, as people moved out of ‘mixed’

areas and into clearly demarcated communities. Did this diminished contact

between the ethnic communities of Belfast have an effect on the phonology of

inner-city speakers? I will address the

question of how variation in phonology is linked to social variation, for

example, differences in age, sex, and location in the city. I will focus on the

inner-city, and will refer to the variety of English spoken there as Belfast

Urban Vernacular (BUV), to distinguish it from more standardised varieties

spoken in the outer-city and suburbs.

Why urban

dialectology?

Why is it

so important, when discussing dialect in the UK, to include the cities? The

dialectologist is often imagined as someone who records rapidly-disappearing

rural forms of language for posterity, the very forms that are being eroded by

the spread of the cities. However, the cities themselves quickly develop their

own dialects, and although the types of English spoken in urban centres are

often among the most stigmatised varieties, even among their own users, urban

or suburban dwellers account for 80% of the population of England (J. Milroy

1981: 4). The figure is lower for Northern Ireland, but still significant.

According to the last census, carried out in 2001, 34% of the country’s

population of 1.6 million live in the Greater Belfast area. The sheer force of

numbers makes studying the dialect of Belfast integral to the study of Northern

Irish English. It is also easier to study the spread of phonological variants

in an area of high population density than it would be in, for example, a rural

area. In a city environment, members from different groups may be placed in

close spatial proximity to each other, whereas in rural settings they choose to

live in different towns and villages. They are also more mobile, and thus less

dependent on the norms of their immediate community to shape their language

practices. There are however, tightly-knit communities established in some

inner-city areas whose members are not mobile, and in this case members will be

much more strongly influenced by the linguistic norms of their immediate

network, rather than the institutional pressures to use ‘correct’ English. This

is a point which I will explore in more detail with reference to the ‘social

network theory’ developed using data from 1970s Belfast.

Walt Wolfram and Natalie Schilling Estes argue that all language is

pre-programmed for change, including phonological change. There is no reason

why the Great Vowel Shift should be regarded any differently from the

phonological variation in BUV. The only difference is that one is a completed

change and one is in progress (91). These changes spread more rapidly in cities

(J Milroy 1981: 5), and are thus easier to observe. The phonological variation

occurring in urban Englishes is often a movement towards some supra-local form,

i.e. dialect levelling, however this does not mean a movement towards the

national standard. For example in their study of the phonology of Tyneside

(Newcastle) English, Dominic Watt and Lesley Milroy conclude that the dialect

is moving towards a ‘northern standard’. However, this standard is very

different from RP, as is ‘Estuary English’, which is becoming a levelled

dialect in the south-east of England (Foulkes and Docherty 43). This

observation can also be applied to Belfast, which is sufficiently

geographically distant from the RP-speaking areas of England that the supposed

‘national standard’ is not regarded as a prestige form.

Why Belfast?

This mental

and geographical isolation of Belfast from England provides an opportunity to

study changes which are occurring from inside the community, rather than as an

attempt to emulate RP. This was reinforced by the effects of sectarian

violence. During the period under discussion, there was very little movement

into the inner-city communities from outside, as they were regarded as too

volatile. Immigration, and immigrant communities, a usual feature of larger

cities, and one which can have a linguistic influence on the local dialect,

were almost non-existent. In general, Belfast dialect is stigmatised, regarded

as inferior and incorrect, and it is the standard variety of Northern Irish

English that is taught in schools, associated with the middle and upper

classes, and presented as the key to social and economic advancement. BUV has

persisted despite these pressures. The static nature of these communities,

clearly demarcated, with little movement in or out, makes it much easier to

isolate phonological changes and pinpoint where they might be coming from.

The linguistic studies of BUV in the

1970s were carried out at a time when ethnicity was becoming much more of a

concern in Belfast. As tensions between the Protestant and Catholic communities

grew, it became more necessary than ever to display ‘allegiance’, to know who

was part of your community and who was an ‘outsider’. Wolfram and

Schilling-Estes claim that periods like this, when language users are concerned

with issues of nationality and community, they will become much more aware of

their use of language and how this differs from others outside their community.

Awareness of dialect difference may be connected with “a growing self- or

group- awareness. Thus, members of a particular social group may seize upon

language differences as part of consciousness raising” (17). In 1970s Belfast,

language variations that had been mere regional markers began to be

reformulated as markers of ethnicity. Belfast in this period provides an

example of how an urban dialect can persist and undergo change, despite being

stigmatised and largely isolated from outside contact.

Ethnic self-identification of BUV speakers

First it

may be useful to clarify exactly what I mean in this article by ‘ethnicity’. We

are used to regarding ‘ethnicity’ as nearly synonymous with ‘race’, but this

meaning is redundant when discussing a country in which 99% of inhabitants

identified themselves as ‘white’ in the last census. Kevin McCafferty provides

a definition of ethnicity that can be applied to a Northern Irish context in

his book, Ethnicity and Language Change,

where he quotes from the sociologist T.H. Eriksen:

Ethnicity….should be taken to mean the systematic and enduring social

reproduction of basic classificatory differences between categories of people

who perceive each other as being culturally discrete (quoted in McCafferty 71).

In other

words, if the Protestant community and the Catholic community perceive themselves as being separate and

different from each other in terms of religion, politics, national allegiances

and cultural practices, and continually reinforce and reinscribe these

differences, then they are different

ethnicities. Ethnicity, in a Northern Irish context, refers to this complex web

of self-definition and group identification, rather than a simple divide based

on religious practice.

The patterns of ethnic division in

Belfast are largely a result of waves of immigration by different groups, from

different areas, at different times. It may seem facetious to discuss the

events of several hundred years ago in relation to linguistic behaviour in

Belfast in the last thirty years, but as Jonathan Bardon points out in his

history of Belfast, the community boundaries have hardly changed since they

first developed. Voting patterns are still shaped by the original settlement

and immigration patterns, so it seems reasonable to assume that linguistic

behaviour in different areas of Belfast will still be strongly influenced by

where the people in those areas originally came from (Bardon 12).

Origins of BUV speakers

Belfast was

founded at the mouth of the River Lagan by English and Scottish settlers in the

early seventeenth century. The crown saw plantation as a means to discourage

further rebellion and to diminish the possibility that Catholic Spain might use

Ireland as a base to attack England. By the 1660s, Belfast was the most

important port in Ulster (Bardon 18). Across the river was the town of

Ballymacarrett, which would eventually be absorbed into Belfast City (becoming

part of East Belfast). The town was peaceful compared to the rest of the

region, as Catholics were a tiny minority in Belfast, too few and too poor to

be considered a threat.

This situation changed with the population explosion of the city in the

industrial revolution. Belfast became a centre for industry, first for linen

weaving, then cotton, then shipbuilding and engineering. The inhabitants of the

surrounding countryside were drawn in by the possibility of work in the city

and the famine and destitution of the countryside. The population soared from

19,000 in 1801 to 70,447 in 1841 and the city pushed westwards. By 1840, a

third of the population was Catholic and tension grew between the two

communities as the city grew overcrowded. Segregated working-class districts

began to develop in the inner-city as the more prosperous inhabitants of

Belfast migrated to the suburbs. The penal laws preventing Catholics from

owning large amounts of land mean that the ‘prosperous’ were almost always

Protestant. This left the inner-city districts to be populated by the

remaining, poorer Protestants and Catholics. BUV as a dialect is a class-specific

accent: most of its speakers are working-class.

Belfast developed into two areas, divided by the River Lagan: West

Belfast, which was predominantly Catholic and East Belfast (containing the

former town of Ballymacarrett), which was predominantly Protestant. It is

useful to bear these origins and ethnic divisions in mind as we examine the

scholarship published about BUV. Sectarian divisions do not produce variant

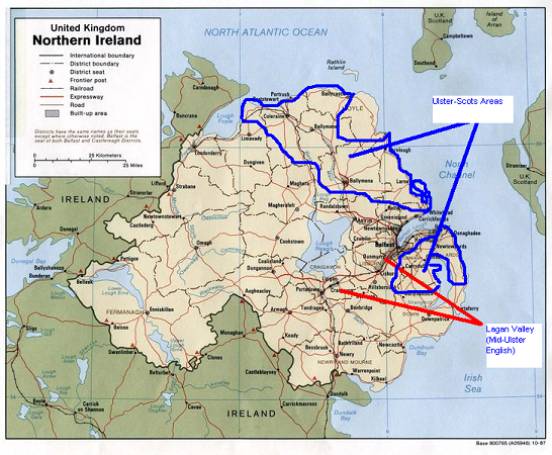

features, but they may reinforce them. East Belfast speech was heavily

influenced by the dialect of the area most of its inhabitants came from, which

was the Ulster-Scots of the mainly Protestant counties, Antrim and Down (see

map below). The Ulster-Scots dialect was a descendent of the dialect spoken by

Scottish settlers, which had been influenced by the surrounding Ulster English.

In fact, the geographical position of the city, sandwiched between these two

Ulster-Scots areas, would suggest that BUV should show much heavier

Ulster-Scots influence than it does. The immigration patterns of the

nineteenth-century are the reason it is more like the speech of Mid-Ulster. In

this period, most people living in the inner city were recent immigrants (in

the 1890s the population grew by a third, 60% of this was due to immigration)

mainly from the Lagan Valley area (J. Milroy 1981: 24). As a result, the speech

of West Belfast is heavily-influenced by the speech of the Lagan Valley, which

in turn was a linguistic descendent of the dialects of English settlers who

planted that area, rather than the

Scottish. John Harris notes that,

The influx of Catholics from the mid-nineteenth century onwards from

south and west Ulster, where the predominant non-Irish influence was English

rather than Scots….and an increase in pressures towards

standardisation…militated against the maintenance of strongly non-standard

Scots forms (Harris 140).

![]()

So, to

summarise: the phonology of West Belfast, which is a majority Catholic area, is

influenced by the dialects of the English who settled in the Lagan Valley, and

the phonology of East Belfast, which is a majority Protestant area, is

influenced by the dialects of the Scottish who settled in Counties Antrim and

Down. However, it is also important to note that ‘more influenced by

Ulster-Scots’ and ‘more influenced by Lagan Valley’ are labels to denote small

differences in what are very similar forms of language which would sound almost

identical to a non-speaker of NIE. It is perhaps more accurate to describe BUV

as a continuum along which these features fall, rather than two clear

‘varieties’. Speakers will be aware of all the variants, but will choose to use

those which most clearly represent their background or allegiance. As James

Milroy puts it,

Dialect is a property of the community, and every native speaker has

roughly the same kind of access to it and roughly the same knowledge about

it….the speakers..know how use the resources of variation available to them,

and they use them for many purposes, including the marking of varying social

roles and functions (J Milroy 1992: 75).

In Belfast, these functions include age, sex,

location within the city (i.e. West/East) and ethnicity.

The Milroy Study: Communities

James and

Lesley Milroy carried out a number of influential studies of Belfast English,

the first in 1977 in the inner-city, and a supplementary study in 1980 in two

outer-city (and lower-middle class rather than working class) communities. I am

focusing on this study as, although thirty years old, it was the last major

study of BUV phonology. It is the 1977 study with which I am mostly concerned

here, as this focused on BUV rather than the outer-city. Many other linguists

have used the data from this fieldwork for their research (for example John

Harris or Ellen Douglas-Cowie – see Bibliography), but none have written on it

as extensively as the Milroys. In this study, they gathered data from three

working-class Belfast districts. Two were in West Belfast (the Clonard - Catholic), and the Hammer - Protestant), and

one was in East Belfast (Ballymacarrett -

Protestant). Their hypotheses were that the tightly-knit, segregated

nature of these inner-city communities would place great pressure on their

members to conform to vernacular linguistic norms rather than aspiring to

standard usage.

In order to foreground the

sociolinguistic conclusions of this study, it is necessary first to outline the

ethnic boundaries and social conditions in the communities in question. As a

Protestant district in a Protestant part of the city, Ballymacarrett is unproblematic.

The situation in West Belfast is more complex. The Clonard is situated on the

Falls Road, and the Hammer is situated on the Shankill Road. Both roads extend

outwards from the city centre, and are only “a few hundred yards apart” at the

inner-city end (J Milroy 1981: 41). At distances this minimal, we would expect

there to be little difference between the speech of the two communities, but it

is important to remember that the communities are segregated, both physically

and culturally. Fredrick Boal’s article, ‘Territoriality on the Shankill-Falls

Divide, Belfast’, provides a snapshot of segregation in the area in 1967-8.

Boal notes that these communities

are separated not only residentially (which is not unusual as “segregation on

the basis of both economic and ethnic characteristics is a feature of most

cities”, Boal 59) but also by ‘activity’, that is, as well as living separately

members do not interact with each other. It is perfectly possible to live in

one of these communities and never encounter members of ‘the other side’,

except in neutral areas such as the shopping districts of the city centre.

Boal’s study was carried out prior to the outbreak of the ‘troubles’ in 1969,

so it is likely this segregation has intensified, with people moving out of

previously mixed areas. One physical barrier that was not present at the time

of Boal’s original study was the “Peace Line”. Barbed wire fences began to be

constructed between the two communities after violent disturbances in 1969.

Today these have been replaced by brick or corrugated iron barriers.

The "Peace

Line", separating the Catholic and Protestant areas of West Belfast. Photo by Kiernan

Joliat, 02 Oct 2004, downloaded 18 Dec 2006 (http://www.pbase.com/sonasgael/image/34627230). Photo governed by

Creative Commons Licence.

Methodology of the Study

Previous

projects designed to gather Irish vernacular speech had been criticised for

their methods. One of these was the Tape-Recorded Survey of Hiberno-English

speech (1973-80). Much of this data consists of exchanges between one

fieldworker and one informant, in which the fieldworker holds the power,

controls the exchanges, sets the agenda and chooses the topics of conversation

(Kirk 68). The informant views the fieldworker as an authority figure, and thus

self-correction towards standard grammar and phonology (in order to seem

‘correct’) is likely. If self-correction occurs, many instances of vernacular

or dialect speech (which is what the study set out to record) will not be

evident, and a skewed picture of vernacular speech will be produced.

In designing the methodology of their projects, the Milroys set out to

address these problems, and minimise the effect of the fieldworker as much as

possible. The researchers relied on mutual acquaintance introductions to gain

access to and move through a community over an extended period. This instilled

some measure of trust and familiarity on the part of the informants and

minimised the self-correction of speech which might have taken place in the

presence of a researcher who was regarded as a complete outsider to the

community. It also avoided the ‘pre-selection’ of more ‘respectable’ (i.e.,

standardised) speakers that might have occurred had the researchers been

introduced through institutional channels (e.g. by teachers, clergymen or

social workers) (J Milroy 1981: 90).

The study consisted of a combination of interviews, reading of

word-lists, and recording of unprompted discussion among informants. This was

intended to capture both formal, interview style (closer to the standard) and a

more spontaneous style (tended to be more vernacular). These were labelled ‘IS’

(Interview Style) and ‘SS’ (spontaneous style). Group discussion was intended

to encourage each informant to speak as he or she normally would in the

presence of the others, i.e. in the vernacular, and to diminish the “perception

of the interview as a speech event subject to clear rules” (L. Milroy 1980:25).

The speech of eight-middle aged people and eight young people was recorded in

each of the three areas (Ballymacarrett, Clonard, Hammer), as well as a random

sample of forty-three households throughout the city, producing a corpus of

over one hundred participants. Additional constraints on the fieldwork

methodology were necessary because of what Lesley Milroy describes as the

“generally disturbed situation” in the city at the time of the research. As

well as forming a connection to the communities in order to establish trust,

the fieldworker had to be a woman and she had to enter the communities alone.

Women were much less likely to be attacked than men, and since male

strangers were at the time viewed with considerable suspicion in many parts of

Belfast, they were likely to be in some danger if they visited one place over a

protracted period. (L. Milroy 1980:44).

Social Network Theory

One of the

questions the Milroys attempted to address in their research was why BUV

persisted against these standardising pressures. The solution they presented to

this problem was that speakers of BUV were experiencing pressures from inside their own community which

operated in the opposite direction from the ideas of prestige and social

improvement that were being imposed from above. Standardising pressures from

the education system and the media were being opposed by counter-prestige that

favoured and enforced vernacular norms. They called this idea ‘social network

theory’.

Pressure to

maintain the vernacular is likely to be strongest in small communities where

almost everyone knows everyone else (a ‘dense’ network), and knows each person

in the network in several capacities (a ‘multiplex’ network). For example,

person A knows person B not only as a friend, but works with him, is related to

him by marriage and lives on the same street. Under these social pressures,

speakers will prefer the solidarity expressed by use of the vernacular, to the

status they might gain by using a more standardised form.

City life is particularly conducive to the formation of strong networks,

as new residents experience an urge to gravitate towards and form ties with

those similar to them. The close-knit network is a form of protection (A.

Giddens, The Constitution of Society,

1984 quoted in J. Milroy and L. Milroy 1992: 7).We might expect this urge to be

even stronger in a city such as Belfast, in which two antagonistic communities

live at close quarters, each feeling threatened by the other. In fact, the

anthropologist Thomas Horjup argues that some degree of insecurity is necessary

in order for strong networks to be formed,

The solidarity ethic would collapse and network ties become weaker if

economic and political conditions allowed workers to feel secure (T Horjup,

quoted in J. Milroy and L. Milroy, 1992: 20).

Dense and multiplex networks are

most likely to form in working-class areas with little turnover in population,

where the inhabitants work together and have ties of kinship L. Milroy and S.

Margrain 48). These factors were taken into account as part of the Milroys’

research, and each informant was assigned a ‘network strength score’ from 0-5

which measured their integration into local networks. A score of zero

represented a person with few strong ties to the local community, whereas a

score of 5 represented someone whose networks within the community were dense

and multiplex (L. Milroy 1980: 139). It is easier for “normative consensus” to

be imposed on speakers who are members of dense, multiplex networks, so these

networks tend to maintain the vernacular and impede linguistic change, whereas

weak networks encourage change and the abandonment or alteration of vernacular

language features (L. Milroy and S. Margrain 48, J. Milroy 1991: 76). In a

dense, multiplex community, using the vernacular is construed as a symbol of

community loyalty, whereas using standard forms is considered

self-aggrandizing, artificial, and a way of disavowing association with the

community and its values.

Conclusions of the Milroys’ research:

phonological variation in Belfast

Now that I

have outlined the methodology and theory behind the research, I will discuss

several phonological features which the Milroys identified as subject to

variation, and question what social trends can be seen as responsible for these

changes in phonology.

The effects of gender roles and community loyalty

on BUV phonology

Ellen

Douglas-Cowie proposes that although both sexes may have the same language

resources in their linguistic repertoire, women engage in more marked

style-shifting and avoid using the vernacular in formal situations. Male

speakers are more likely to cleave to vernacular forms. From this,

Douglas-Cowie suggests that we can categorise women as more innovative in

adopting changes in language, whereas men are more conservative in their

language habits (543). Of course this does not apply to every individual man

and woman, but it is visible as a general trend when the speech of large

numbers of people is analysed. We would expect from this line of thought, that

linguistic change in Belfast would be spearheaded by women.

One long-standing feature of Belfast dialect where the differences between male and female linguistic behaviour can be observed is the distinctive BUV rounded vowel. Vowel rounding means that the standard Northern Irish English [ü], becomes

[ʌ], causing words such as ‘pull’ to be pronounced

to rhyme with ‘dull’, rather than ‘pool’, and words such as ‘shook’ to be

pronounced to rhyme with ‘luck’. David Patterson mentions words with this

variable in his pamphlet; The provincialisms of Belfast pointed

out and corrected

(1860). Although it is a feature that originally entered Belfast speech from

rural dialect, this pronunciation was actually more frequent among young men

than older speakers at the time of the Milroys’ study. James Milroy suggests that

they “feel it is a prominent marker of Belfast dialect, and they use it as a

symbol of community loyalty” (J. Milroy 1981: 30). Perhaps the need to express

allegiance to an inner-city community was strengthened by the severe disruption

caused by the Troubles (which started in 1969) to these communities.

The Milroys gathered data for four groups: men 40-55, women 40-55, men

18-25 and women 18-25. In the older age group, women use the ‘dull’

pronunciation more than men, in both Interview Style (IS) and Spontaneous Style

(SS), however in the 18-25 age group men use the dialectal variant much more

than women. This gender difference is particularly strong in SS, with only 20%

of utterances by women aged 18-25 using the ‘dull’ pronunciation, compared to

61% of those by men in this age group (J. Milroy 1981: 95). So, what was seen

as a stigmatised dialectal variant has become a marker of community identity,

but only for men; why might this be?

James Milroy indicates that both variants may be present in the linguistic

repertoire of the informant, and that the speech of the inner-city shows a high

incidence of “phonolexical alternation” between possibilities (J, Milroy 1991:

78). This can be demonstrated by referring back to the figures for the PULL

variable; in every age and sex grouping, the vernacular pronunciation is used

significantly more in SS than in IS. This suggests that informants are capable

of realising both variants, and which one they select is the result of a choice

based on the formality of the situation, who they are speaking to, who else is

present and the topic of conversation. The alternative choices can also be used

to send social signals, with the vernacular variant encoding “messages of

social nearness” or community with the addressee, whereas the standard variant

encodes “social distance” (J Milroy 1991: 79). Women, however, are much more

likely to use a variant closer to the standard. Every speaker will ‘correct’

his or her speech towards what is perceived to be ‘standard’, but women will do

it to a much greater extent than men. There is no certain explanation for why

this occurs, but James Milroy offers a suggestion:

This is a general truth – not confined to Belfast or any single place.

It may be interpreted to mean that women are more linguistically aware or that

they are better at languages generally: certainly, they do make a greater

effort to use the pronunciation they judge appropriate to the circumstances in

which they are speaking (J. Milroy 1981: 38).

Another variant which is used much more heavily by men than my women is

the deletion of ð, e.g. dropping the ‘th’ sound from words such as ‘mother’ and

‘brother’, so that they become ‘mo’er’ and ‘bro’er’. In the inner-city areas

used in the study, virtually everyone uses this variant to a greater or lesser

extent, but as with the PULL variable, men use the vernacular variant more

often than women in all age groups and styles, and the younger men use it more

than the older men. If we looked solely at the difference between usage by young

men and older men, we might conclude that use of the vernacular form was

spreading, and that today, almost thirty years after the study was carried out,

dropping of ð would be higher still if we were to test it.

However, Milroy points out that by looking at the female scores, we can

tell that ‘th’-dropping is actually stable overall in the community: younger

women use it almost as much as older women. He suggests that the increased use

of the vernacular variant among young men, is a consequence of this group’s

social attitudes. They admire the ‘roughness’ of the vernacular and wish to use

it, but as they grow older and “begin to define their role in society

differently” (e.g. as they get married, become householders and are fully

employed) they shift towards using more standard forms; in this case,

pronouncing ‘th’ (J. Milroy 1981: 36-7). The vernacular pronunciation will

always be used more by young men, but it is not spreading to other groups. This

feature is very strongly sex-marked: when relevant words were spoken, young men

dropped the ‘th’ 80% of the time in SS and 89% in IS, whereas young women only

dropped it 47% of the time in SS and 30% in IS.

/A/ backing, is a another phonological feature which is strongly

affected by gender roles and community ties. In this feature, the pronunciation

of /a/ is moved backwards in the mouth, so for example, ‘hand’, man’ and lad

become ‘haund’, ‘maun’ and ‘laud’. At the time of the study, /a/ backing was

most prevalent among East Belfast males, however it was spreading to West

Belfast. The discovery that men use the vernacular variant more is not

surprising. Ballymacarrett is an area that was heavily influenced by the

shipyards. In this community unemployment was low, gender roles were clearly

differentiated (hence the corresponding lack of use of backed /a/ by women) and

most families had been in the area for generations. Most of the men in the area

were employed in shipbuilding, and according to the social network theory these

conditions are exactly those which tend to create strong, multiplex networks

(the men lived in the same area and worked together). The stronger and more

multiplex the network, the more pressure to maintain vernacular forms. Backing

of /a/ was being used to encode meanings of informality, social proximity and

male identity. One question worth addressing in any future studies of

Ballymacarrett is whether the decline of the shipyards as an employer in the

area (from over 30,000 employees in the 1970s in to 130 in 2003, BBC News) has

led to a weakening of networks and an erosion of vernacular language features.

The Spread of Vernacular Features across the

City.

The figures

provided by John Harris (221) show that among older men, ‘th’ dropping is much

more prevalent in Ballymacarrett. Here 89% dropping occurs in SS, as opposed to

56% in the Hammer and 62% in the Clonard. On the basis of these figures, we

might conclude that it is a feature of East Belfast dialect, however among

young men it is equally prevalent in all three areas. This suggests that the

feature started in the East of the city and has spread from East to West. The

situation becomes more interesting when we compare female scores across the

three areas. Although scores for young women are lower than those for young men

in all cases, the scores for young women in the Clonard are significantly

higher than those for young women in Ballymacarrett (SS: B 15%, H 57%, C 70%).

This confuses the theory of ð deletion as a clearly East Belfast feature. What

we can say is that it is a feature that in East Belfast is heavily used by men,

and it has spread to young West Belfast men and women, with disproportionately

high figures among young women in the Clonard. Might this be because young

women were the group who introduced the feature to West Belfast, and why might

they be particularly likely to be linguistic innovators? I will return to this

question in more detail after a discussion of whether language features vary

based on ethnicity.

Phonology and Ethnicity – can they be linked?

One of the

features that is often identified as Catholic is palatalisation, i.e.

pronunciation of a ‘y’ sound after initial ‘k’ and ‘g’ sounds, i.e. ‘car’ is

pronounced as ‘kyar’, and gas as ‘gyas’. However, Milroy argues that the origin

of the speech community is more important in determining whether speakers

palatalise or not than the ethnicity of the speaker. In Northern Ireland, some

areas have a majority of Catholics and some have majority of Protestants. As I

mentioned earlier in this article, the Ulster-Scots, from which the people in

East Belfast mainly came, are heavily Protestant, so Ulster-Scots features will

lead a listener who is aware of these regional divides to hypothesise that the

speaker is Protestant. Likewise, West Belfast was mainly populated from the Lagan

Valley and west and south Ulster, where there are more Catholics and

palatalisation is more common. Thus, palatalisation might lead a listener to

guess that the speaker is Catholic. Linguistic clues can be used to guess at

ethnicity, but this is not to say that ethnicity produces phonology, simply that knowing the phonology of different

regions, and the ethnic make-up of those regions, can lead the listener to an

educated guess. As James Milroy puts it,

There is a fairly high probability that you will be right if you

identify a South Armagh speaker as a Catholic and a North Down speaker as a

Protestant, but this is obviously only a probability and not a certainty (J

Milroy 1981: 42).

A minority

Catholic speaker from an Ulster-Scots area will still use Ulster-Scots

phonology, although this is associated with Protestantism.

To return to Belfast, on the basis

of the immigration patterns that formed the areas we would predict that East

Belfast pronunciations would be identified as Ulster-Scots-influenced and

therefore Protestant, whereas West Belfast pronunciations would be identified

as influenced by west and south Ulster, and therefore more likely to be

Catholic. However, it is necessary to remember that there are communities of

Protestants living in West Belfast, the Hammer being one of them. Do these

Protestants palatalise or not? Are they more like the Catholics who live in

close proximity to them in West Belfast, or like the Protestants across the

river?

The answer is that they are

somewhere between. Harris notes that palatalisation is a recessive feature that

is “now almost entirely restricted to older male speakers” (214). Accordingly,

the older men in the Clonard are the ones that use it the most (62% of times

when reading a word-list), while Ballymacarrett men in this age group do not

use it at all. Men from the Hammer use it much less than their neighbours in

the Clonard (14%). There are no figures available to measure whether men in the

Hammer have been palatalising less over time, but it is likely that the

presence of the “Peace Line” dividing them from the Clonard might have caused

divergence between the communities since the time of the research. However, the

Hammer men are palatalising, whereas

men in Ballymacarrett are not doing it at all, which would seem to suggest that

it is a West Belfast feature rather than solely a ‘Catholic’ one. Also, neither

the Milroys nor Harris provide any figures for palatalisation in IS. It is

possible that the feature, which is stigmatised as rural, might appear more in

unguarded, spontaneous speech.

How ‘weak’ ties facilitate language change

I mentioned

that the backed /a/ feature originated in Ballymacarrett. Only one group in

West Belfast were using backed /a/ more

than their counterparts in Ballymacarrett: the young women in the Clonard (J.

Milroy 1992: 186). This group of women appeared earlier as possible innovators

in connection with the variable ð. Women in this area are actually using the

vernacular variant more than young men in the same area. Why might this be? How

could young Catholic women be picking up a stereotypically Protestant, male

pronunciation when the “Peace Line” divides their communities?

James Milroy’s answer to this is to refer to Mark Granovetter’s theory

of how weak ties operate. Granovetter argued that although strong ties maintain

vernacular norms within a community, weak ties are a “crucial bridge” between

communities. Weak ties connect us to people different from ourselves, outside

our immediate community, and are a conduit through which linguistic change may

be spread (Granovetter 106, 108). Social conditions in the Clonard and Hammer

(which also shows a high incidence of female /a/ backing, although not as high

as the Clonard) were quite different at the time of the study from those in

Ballymacarrett. There was no cohesive industry, and male unemployment rates

were around 35%. Lesley Milroy claims that “women were much more inclined than

men to look for work outside the locality”, often earning the family wage. As a

result, gender roles were much less clearly marked than those in Ballymacarrett

(L. Milroy 1982: 162). The women often found jobs outside the community at

city-centre shops, were they were in weak-tie contact with “large numbers of

people from all over the city, both Catholic and Protestant” (J. Milroy 1992:

187). East Belfast phonologies picked up from the many weak contacts they might

have in their employment could then be spread back into their own community.

Conclusions

These

studies demonstrate that in the Belfast of 1977, phonological variants were

clearly being used as social markers. To choose a vernacular variant over a

standard one was an expression of solidarity with a particular local identity.

Which variants speakers used depended on their sex, their age, their location

within the city, the origins of their speech community and the strength of the

networks in their area. There was stronger pressure in East Belfast to adhere

to vernacular norms, particularly among young men, but the greater mobility of

young women within the city meant that they were the speakers who carried

linguistic change over barriers between the communities. As much as this

research can tell us about BUV phonology, it is almost thirty years after the

research was carried out. It is reasonable to assume that it is now outdated,

and new research is needed to investigate the effects thirty years of

segregation have had on these communities and their speech. This research might

investigate whether gender differences are still clearly marked in BUV, and

whether the diffusion of features from one side of the city to the other has

continued at the same rate or been slowed down by segregation.

Works

Cited

Bardon, Jonathan. Belfast: An Illustrated History. Dundonald, Belfast:

Blackstaff Press, 1982.

BBC News. “Cranes to remain on city skyline”.

Thurs. 9 Oct 2003.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/3176184.stm> , accessed 19

Oct 2006.

Boal, Frederick W. “Territoriality on the

Shankill-Falls Divide, Belfast: The Perspective from 1976”. An Invitation to Geography (2nd

ed.). Ed. David A. Lanegran and Risa Palm. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978.

58-77.

Douglas-Cowie, Ellen. "The sociolinguistic

situation in Northern Ireland”. Language

in the British Isles. Ed. Peter Trudgill. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1984. 533-545.

Foulkes, Paul and Gerard Docherty. Urban Voices: Accent Studies in the British

Isles. London: Arnold, 1999.

Granovetter, Mark. “The Strength of Weak Ties:

A Network Theory Revisited”. Social

Structure and Network Analysis. Ed. Peter V. Marsden and Nan Lin. Beverly

Hills/London/New Dehli: Sage, 1982.

Harris, John. Phonological Variation and Change. Studies in

Hiberno-English, Cambridge Studies in Linguistics, Supplementary Volume.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Kirk, John M. “The Northern Ireland Transcribed

Corpus of Speech”. New Directions in

English Language Corpora: Methodology, Results, Software Developments. Ed.

Gerhard Leitner. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyer, 1992. 65-73.

McCafferty, Kevin. Ethnicity and Language Change: English in (London)Derry, Northern

Ireland. Impact: Studies in Language and Society. Amsterdam and

Philadephia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2001.

Milroy, James. Regional Accents of English: Belfast. Dundonald, Belfast:

Blackstaff Press, 1981.

----“The Interpretation of Social Constraints

on Variation in Belfast English”. English

around the world: sociolinguistic perspectives. Ed. Jenny Cheshire.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. 75-85.

----Linguistic

variation and change. On the historical sociolinguistics of English. Book.

Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

Milroy, James and Lesley Milroy. “Social

Network and Social Class: Toward an Integrated Sociolinguistic Model”. Language in Society, vol.21, no.1

(1992). 1-26.

Milroy, Lesley. Language and Social Networks. Language in Society 2. Oxford:

Blackwell, 1980.

Milroy, Lesley. “The Effect of Two Interacting Extra Linguistic Variables on Patterns of Variation in Urban Vernacular Speech”. Variation Omnibus. Ed. David Sankoff and Henrietta Cedergren. Edmonton, Alberta: Linguistic Research, Inc., 1982. 161-170.

Milroy, Lesley and Sue Margrain. “Vernacular Language Loyalty and Social

Network”. Language in Society, vol.

9, no. 1 (1980). 43-70.

Northern Ireland Statistics and Research

Agency. Northern Ireland Census 2001.

< <http://www.nicensus2001.gov.uk>,

accessed 28 Nov 2006.

Patterson, David. The provincialisms of Belfast pointed out and corrected. Belfast:

Mayne, 1860.

Wolfram, Walt and Natalie Schilling-Estes. American English: Dialects and Variation, Language in Society 24. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998.